Impact of Migration: Rittindai Hills, Ukusmukus in Terai

As living in the hills becomes more difficult, people are fleeing in droves abandoning their villages. As a result, while farmlands have been left desolate and abandoned in the hills, land is increasingly getting fragmented in the lowlands, and population pressure is rising in the cities.

When most of the people moved out of Andheri village in Dhankuta, members of only one household remained – that of Gopal and Rupa Pariyar. Every day, Gopal commutes an hour to the Friday market, where he works as a sewing labourer. When Gopal and her two school-age children leave, Rupa finds herself alone in the village.

The nearest settlement from Andheri is a 30-minute walk away. As Rupa leaves the village to fetch water from a half-hour away source, the whole village gets deserted.

Chaubise Rural Municipality-3 had 20 houses a decade ago. “The community was active, with farms, and neighbours lent each other hands through their struggles and celebrated festivals together,” Gopal recalls. The community is now surrounded by quiet.

House in ruins in Chaubise, Dhankuta. Photos: Gopal Dahal

Gopal’s neighbours, including Rajendra Khadka, Bhala Chapagain, Madhav Chapagain, and Chetanath Baral, gradually left Andheri. Some moved to the Dhankuta Bazaar, while others relocated to the Terai. As a result, the once-vibrant village has now turned into a forest.

The settlement abandoned by people has turned into a playground for monkeys. The Pariyars face difficulties growing vegetables as monkeys come eat whatever they grow. Gopal complains about being alone, cooking and eating festival food by himself, and having no one to count on when he’s unwell.

Gopal says, folks who made money overseas or improved their financial status at home bought land in Terai and moved there. But Gopal didn’t have the means to relocate.

Ward No. 4 in neighbouring Kafle village has also been fully vacated, with all 12 houses abandoned. Overgrowth has taken up courtyards and gardens. In Thulagaun, Choubise, after 22 households fled, just four families remain.

Dandagaon, Garigaon, and Bajthala in Choubise-3 are also desolate. These areas have turned into ghost towns with abandoned houses, overgrown plants, and weeds. Ward chairman of Chaubise-3, Madan Tumsa, says that despite their attempts, they have been unable to stem migration, and the villages are crumbling.

People are increasingly leaving rural communities; this trend is accelerating. In 2020, 432 people from 160 families in Choubise moved out. The number increased to 196 houses and 546 people the following year. A total of 561 people from 185 houses had left as of November 2022. Only those who received a migration certificate from the rural municipality are included in this data; many more people relocate without telling the local government.

Tankamaya Pangmi, deputy head of a rural municipality, voiced concern about the situation of Magar villages, stating, “We talk about development, yet the people come to us in droves to get migration certificates.”

“It breaks my heart to watch people move out abandoning their ancestral homes,” she continued.

The migration trend is not just evident in remote settlements in the eastern highlands; it is also evident in Dhankuta, former administrative centre of Eastern Development Zone. The office of the Bada Hakim, appointed by the Ranas, was once located at Dhankuta. As people would come to the market from adjacent villages to buy everything, it used to be a hive of activity. Unfortunately, Dhankuta’s appeal has now diminished, and many of the once-active shops in Lower and Upper Kopche’s bustling marketplaces have shut. Because there are no buyers, trade is limited and merchants have also moved out.

“Though many discussions have been held on preventing people from moving out, it hasn’t been possible to stop migrants looking for better facilities,” said Sabitra Rai, deputy head of the District Coordination Committee, Dhankuta.

An abandoned house in Chaubise, Dhankuta.

The situation with regard to migration is considerably worse if we look at the nearby region of Tehrathum. Tehrathum used to have 32 villages, but currently there are just two municipalities and four rural municipalities. Myanglung municipality has been at the forefront of the migration crisis. As fewer customers visit the market, traders have been forced to relocate. As everyone wants to sell their land, prices have hit rock-bottom and the fields have gone barren.

Up until a decade ago, Laliguras Municipality’s Basantapur market was a well-liked destination. Its state right now, nevertheless, is identical to that of Manglung. Laliguras is one of the five municipalities in the country with the lowest population.

According to the 2001 census, the population of Tehrathum was 113,111. However, by 2011, the population had decreased to 101,577. As of 2021, the population is limited to 89,125.

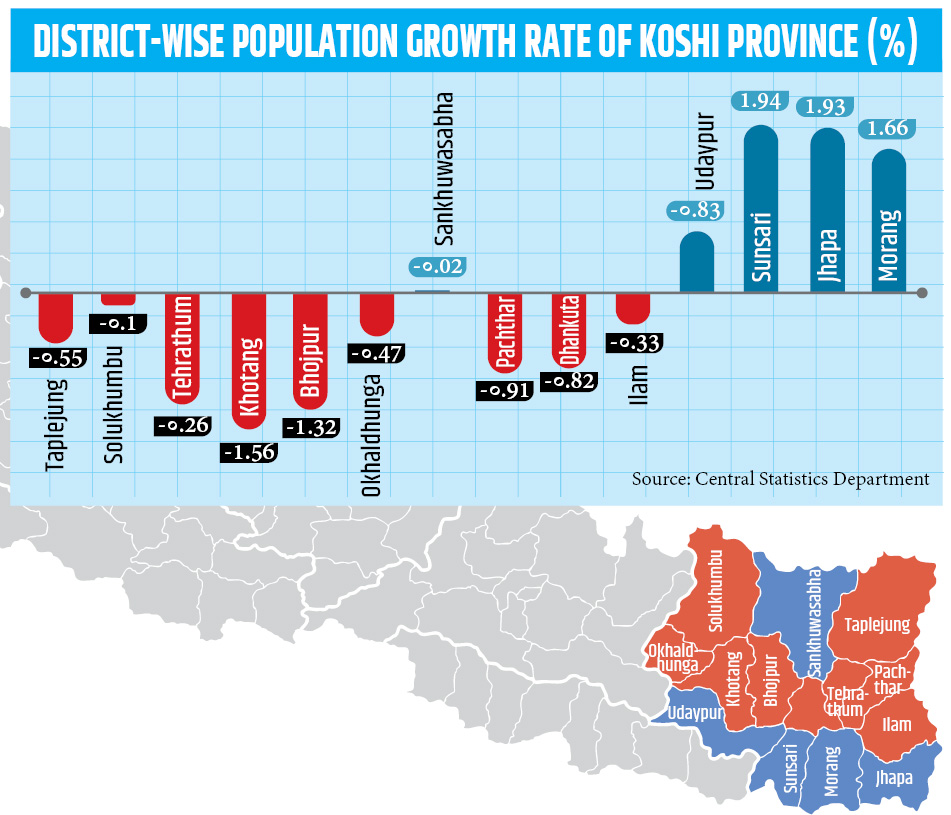

Preliminary data from the National Census of 2021 has shown that most of the districts with negative annual population growth rate are in the Eastern hills.

According to the data, of the 32 districts with a negative population growth rate, nine are in Koshi Province: Khotang, Bhojpur, Tehrathum, Panchthar, Dhankuta, Taplejung, Okhaldhunga, Ilam, and Solukhumbu. Among these districts, Khotang (-1.56 percent), Bhojpur (-1.32 percent), and Tehrathum (-1.26 percent) in the province have seen the highest population decline over the past 10 years.

The population in 75 villages and municipalities across Koshi Province has declined over the past ten years, apart from Jhapa, Morang, and Sunsari located in the Terai. Head of the Statistics Office, Morang, Tirtha Baral, analysed the population decline in the eastern hills and found that migration is the main reason behind the phenomenon.

Baral said, “Although the population of the country as a whole has risen, the main reason behind the population drop in the Himalayan and mountainous areas is migration. If the birth rate had fallen or the death rate had increased, the population would have remained steady.”

Why are villages getting deserted?

According to the ‘District Profile’ prepared by the Tehrathum District Development Committee in 2014, the rate of migration from rural to urban areas, as well as from urban areas to areas to the Terai, is on the rise as a result of factors such as poverty, a lack of opportunities, and problems with peace and security in rural areas.

The assertion is still true after eight years. The major factors attributed for the migration of people from the hills to the plains are the quest for improved health, education, and employment prospects. This tendency is also influenced by a number of social, economic, and political issues.

Anthropologist Suresh Dhakal said people migrate for various reasons. The universal trend is to move towards places with better facilities and amenities, which enables people to lead comfortable lives.

Sociologist Ram Gurung sys that the opening of the jute mill in Biratnagar in 1936 led to increased migration and the development of the eastern part of Nepal (Kahar Baneko Sahar. Himal Khabarpatrika, 2079 Mangshir). Additionally, analysis shows that migration from the eastern hills to the plains has continued to rise since the 1970s.

Many lahure families moved into cities such as Dharan, Itahari, and Damak from Khotang, Bhojpur,Tehrathum, and Taplejung as a result of the establishment of the recruitment center for Gurkhas in Dharan in 1953. This lured people to settle in these towns and they encouraged their relatives to do so as well. Those returning from work abroad have started to noticeably move to the Terai region in recent years.

During the Maoist insurgency, there was a huge rise in the number of people relocating to cities from villages and the Terai from the hills and mountains. This pattern continues to this day.

In recent times, a growing number of individuals have been forced to migrate out of impoverished villages in Bhojpur and Khotang districts due to a variety of challenges, including the inability to protect their crops from monkeys and a lack of access to drinking water.

Sudan Kiranti, an elected MP from Bhojpur and current Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation, raised concerns about this trend in Parliament three years ago. Kiranti lamented that individuals were being forced to migrate due to lack of access to essential services such as education, healthcare, and drinking water.

He also highlighted the dire living conditions faced by those who remain in their villages, including the threat posed by monkeys, who were known to steal rice cooking pots from inside people’s homes. Kiranti expressed his disappointment that these issues had not been adequately addressed in the budget and called for greater attention to be paid to the needs of rural communities.

Tehrathum district in Nepal has witnessed a growing trend of people migrating from villages such as Hamarjung, Panchkanya, Okhre, Tamphula, Jaljale, Isibu, Chuhandanda, Chatedhunga, and other areas due to a range of challenges such as water scarcity, monkey menace, and unemployment.

Santabir Limbu, chairman of Chhathar Rural Municipality of Tehrathum, said the outflow of migrants can be attributed to a range of factors. Some individuals are forced to migrate due to the scarcity of basic necessities such as water, while others are in search of better economic opportunities.

The Choubise-3 family of Gopal and Rupa Pariyar, who are now living alone due to the eviction of their neighbors.

Arjun Mabohang, head of Laliguras Municipality, says, “Be it a teacher or an employee or a leader, once they start earning, they move to the city. There are only children and old people in the village. The hills are being deserted day by day.”

Caste discrimination and untouchability continue to be a significant issue in many rural areas of Nepal, forcing some individuals to migrate to cities in search of better living conditions and opportunities. This reality has been highlighted by Khilnath BK, a journalist and teacher who left Bhojpur and settled in Dharan after being unable to endure discrimination in his village.

BK, who is educated, said, “In the village, there is more caste discrimination than in the city. For educated people like us, it is unbearable,” he said.

Tankamaya Pangmi, deputy head of Chaubise Rural Municipality, Dhankuta, highlights that the reasons behind the migration of Magar from the village are varied and complex. Pangmi cites numerous factors such as poor infrastructure, lack of access to basic services, and inadequate educational and healthcare facilities. During the rainy season, dirt roads in the village become inaccessible, making transportation difficult and hindering the delivery of village produce to the market. Pangmi notes that the absence of proper medical facilities, schools and water supply in the village further motivates people to migrate to urban areas.

Despite the promises made by political parties to decentralise power and promote development across all parts of Nepal after the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015, the reality in many villages paints a different picture. Even after five years of federalism, the promised “Singh Darbar in villages” vision remains elusive.

Prakash Kumar Adhikari, head of the statistics office in Dhankuta, has been closely monitoring the situation in hill villages. Adhikari said that although the introduction of empowered local levels has been a positive step, it hasn’t translated into significant development on the ground. “Despite the promises made after federalism, there has been little to no development in the hills,” he asserts.

Bijyanbabu Regmi, an expert in development economics, said while federalism has improved some aspects of government work, it hasn’t been sufficient to address the challenges faced by rural communities. “The primary reason for migration worldwide is economic and social security. Despite the implementation of federalism, the economic conditions for those living in rural areas have not improved. Much of the budget allocated to local levels is being spent on unproductive projects,” Regmi explains.

Despite education and health being guaranteed as fundamental rights in the Constitution of Nepal, hilly areas lack well-equipped hospitals and skilled doctors. The absence of such essential resources has led to the compulsion for locals to travel to the city for general surgeries or plastering of broken limbs.

Laligurans municipality of Tehrathum bought x-ray and video x-ray machines, but couldn’t find a doctor to look at reports generated by the machines. City chief Mabohang says, “The roads in the hills aren’t good, if you try to take a pregnant woman to the hospital, she will die while waiting for the ambulance.” That’s what happened on January 4, when 19-year-old expecting mother Manisha Acharya of Panchthar’s Kumyak-2 died due to hemorrhage.

Educational institutions in the Himalayan and hilly regions of Nepal are in a critical state, and many families prioritise moving to the city for quality education for their children. Even young people who have returned from foreign employment are reluctant to go back to their hometowns in the hills due to the lack of proper educational facilities.

According to Kumar Karki, president of Nepal Settlement Protection Society, the compulsion of those who leave their mountain houses barren and become squatters in Terai cities is also to find ease of living. He says, “There is no doctor when you are sick in the village, there is no good school to educate your children. One can make a living by doing some work in the city.”

Population piles up

The urban areas of Sunsari, Morang, and Jhapa are the primary destination for those migrating from the Himalayan and hilly regions of Koshi Province, according to census data. Sunsari, in particular, is among the top five districts with the highest population density in the country. In fact, its population growth rate is even higher than that of Kathmandu. The latest census shows that while Kathmandu’s annual population growth rate is 1.40 percent, Sunsari’s is 1.94 percent. Similarly, Morang has a growth rate of 1.66 percent and Jhapa has a growth rate of 1.93 percent, far higher than the overall country’s annual population growth rate of 0.93 percent.

According to the census data, Sunsari district’s population increased significantly from 763,487 in 2011 to 934,461 in 2021. This makes Sunsari one of the five districts with the highest population in the country, alongside Morang, Jhapa, Kathmandu, and Rupandehi.

Remnants of the demolished home after the owner left.

Prakash Kumar Adhikari, head of Statistics Office Dhankuta, expressed concern over the imbalanced population distribution in Koshi Province to migration from hill districts to Terai districts. He points out, “The mountains and hills are becoming depopulated while the population is rapidly increasing in the plains, which is an alarming trend.”

Not only in Koshi Province, the population of Himalayan and hilly areas is decreasing and the population of Terai is increasing all over the country. According to the data from ‘Nepal Labor Survey 2017/18’ released by the Central Bureau of Statistics (currently the National Statistics Office), 36.2 percent of people live in a different place than where they were born. This data confirms that the country’s population is moving.

The population growth rate in the Himalayan region of Nepal was negative (-0.02%) during the 10 years, while the hilly region had a small positive growth rate of 0.29% during the same period. In contrast, the Terai region had a high positive growth rate of 1.56%. These numbers indicate a trend of people migrating from the hills and mountains to the Terai region.

Uncontrolled migration from the mountains and hills is considered by Karki, president of the squatters’ organisation, Nepal Settlement Protection Society, as the main reason for the squatters’ problems and informal settlements in the urban areas of the country. He claims, “About 60 percent of the informal squatters living on river banks across the country are people who migrated from the Himalayan and mountainous areas because they were unable to lead a normal life.”

Most of the squatters living on the banks of Sardu and Seuti rivers in Dharan are found to have come from the eastern hill districts. One of them is Manmaya Tamang. Her family, originally from Bhojpur, came to the shores of Sardu as life there was not easy. Tamang says, “There is nothing to eat in the mountains, here you can fill your stomach even if you just crush the gravel.” We are living on the banks of the river not because we want to. We don’t have any other option.”

Government policy

The government has reportedly found advantages in designating remote settlements as municipalities instead of focusing on village development. This move has led to a surge in the country’s urban population, which now stands at 66.08 percent.

In an announcement made 12 years ago, the Nepali government declared plans to construct 10 new cities along the Midhill highway, including Phidim in Panchthar and Basantpur in Tehrathum. However, the plan has remained stalled, and the number of proposed cities has since increased to 54. Despite a target of reaching a population of 100,000 within 20 years, it appears unlikely to be met due to the decreasing population in the hills each year.

The population of Phidim Municipality in Panchthar currently stands at 48,713 while Laligurans Municipality, which includes Basantpur Bazaar in Tehrathum, has a population of only 15,418. Despite government efforts to step-up urbanisation, local officials are concerned that imposing urban standards in these mountainous regions could lead to the destruction of local markets. Mabohang, chief of Laligurans Municipality, questioned how development can occur without considering the needs of the local population.

The Midhill Highway, which connects hill settlements, is required to have a width of 31-31 meters offset on both sides of the road as per the Public Roads Act, 1974. However, extending the highway to meet these standards will require demolition of market areas along the way.

According to the on-site study and observation report conducted by the Development and Technology Committee of the House of Representatives from May 21-25, 2019 on the eastern section of the highway, it was recommended that the standards should be reduced and maintained at 15×15 meters from the middle of the road in most places including Panchthar, Tehrathum, and Dhankuta. This report suggests that reducing the width of the highway is necessary to avoid the displacement of hill settlements and protect the hill markets.

Inadequate efforts to retain population

Despite the efforts made by the local authorities to curb the rising migration, it seems to be insufficient.

In a bid to boost its population, Chhathar Jorpati Rural Municipality in Dhankuta is offering cows as gifts to individuals who migrate to their area. The move is aimed at attracting more people to the region, and increasing its population.

Meanwhile, the Chaubise Rural Municipality in Dhankuta is taking steps to address the water scarcity in some areas.

Even though his neighbors left the village, Gopikrishna Bhandari of Dhankuta, Choubise, began a goat farm with the intention of expanding it. Photo: Bhandari family

Vice-chair Sabitra Rai announced that the Dhankuta District Coordinating Committee has initiated the “One Municipality One Technical School” policy after thorough discussions with all municipalities in the district. The aim of this program is to encourage the youth who move to the Terai for education to stay in the village by providing them with technical education opportunities.

Chhathar Rural Municipality in Tehrathum announced in the financial year 2018/19 a reward of Rs 100,000 and a commercial grant of up to half a million rupees for those who migrate to the village from other places. As a result, 34 families have migrated to the village after a 16-kilometer pipeline was laid to bring water from Telia and Dhandkhola. Santabir Limbu, the village head, says, “Understanding the needs of the people can prevent migration. However, he emphasizes that the provincial and federal governments should develop quality health and education in the villages and create job opportunities.”

Mabohang, head of Laligurans municipality, said, “The provincial and federal government budgets are primarily focused on the cities due to the influence of big leaders and government employees who have migrated from the mountains and hills. As a result, development in the mountains and hills is not a priority for these leaders.”

Mabohang is of the opinion that migration can be reduced if the villagers’ living conditions are made easier by doing things like infrastructure development, quality education and provision of medicine even from the limited budget of the local level.

The recently released budget for Koshi Province for 2022/23 has allocated funds for the development of Biratnagar, Itahari, and Dharan, with a master plan for larger development in these cities. However, no such plan has been proposed for the hilly areas of the province.

The focus of health, education, and infrastructure development plans is primarily on Jhapa, Morang, and Sunsari. For instance, the province allocated Rs.21 million for science teacher grants and science laboratories in each district, whereas only Rs.17 million was allocated for Manmohan Technical University in Morang only, as per the government’s efforts to turn it into a model for South Asia. Furthermore, even the federal government’s major plans are city-centric, disregarding the needs of rural areas.

Indra Bahadur Angbo, outgoing Minister of Economic Affairs and Planning of Koshi Province, admits that the budget is also concentrated in the cities, as people with access to power live there. He says, “In order to ensure health, education and employment in the village, it is necessary to make a policy together with the local, state and federal governments.”

Mabohang, head of Laliguras Municipality, believes that the government can significantly reduce migration from the hills by establishing three or four municipalities in the region and providing quality healthcare and education facilities. He said, “The divide is no longer between the rich and the poor, but between those living in villages and cities. The government should implement a policy of reservation for individuals from rural areas.”

According to Karki, central president of the Nepal Settlement Protection Society, the key to stopping migration from the mountains lies in the development of education, health, and infrastructure in the villages. He highlights the case of 24 squatter families who migrated from Itahari after the construction of the Tamor Corridor under the Midhill Highway. “When we focus our development work in the cities, we can’t complain that villages are getting deserted.”

According to a recent report on economic activity published by the National Banijya Bank, Biratnagar, the increased migration from the hilly areas to the Terai has led to the degradation of fertile land in the hills and increased fragmentation of arable land in the plains. The report highlights the difficulty of cultivating crops on barren land in the hills and the need to prevent further fragmentation of land in the plains.

Regmi, a development economics expert, said policymakers should focus on attracting the section of the village population that seeks to move away from agriculture. He emphasizes the need to establish small industries in villages and invest in infrastructure, as well as improve the quality of healthcare and education.

Jagdishchandra Pokharel, former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission and a regional development expert, said expanding production and facilities in rural areas is crucial to connecting villages with urban centers.

Chief Minister of Koshi Province, Hikmat Karki, said the province’s limited jurisdiction and budget have led to uneven development, resulting in growing migration from rural areas. “We are concerned over this trend,” he said. “We need coordinated efforts from the state and union governments to implement employment programs and to work with the federal government to improve health, education, and infrastructure in rural areas.”

Four families from Choubise-3 village in Dhankuta have chosen to stay back, despite 22 others migrating to other places in search of better opportunities. Gopikrishna Bhandari, one of the villagers staying put, said, “We don’t expect much from the government. All we want is basic services and support for those who want to stay in the villages. If all that is there, who would want to leave their ancestral land!”

Comments