Dignified Menstruation: Paving the way for women empowerment

The pressing need for positive change in addressing menstrual hygiene and eradicating harmful traditions, it is crucial to recognize the intersectionality of the issue. Menstruation is not only a gender-specific concern but also a matter of social, economic, and environmental justice.

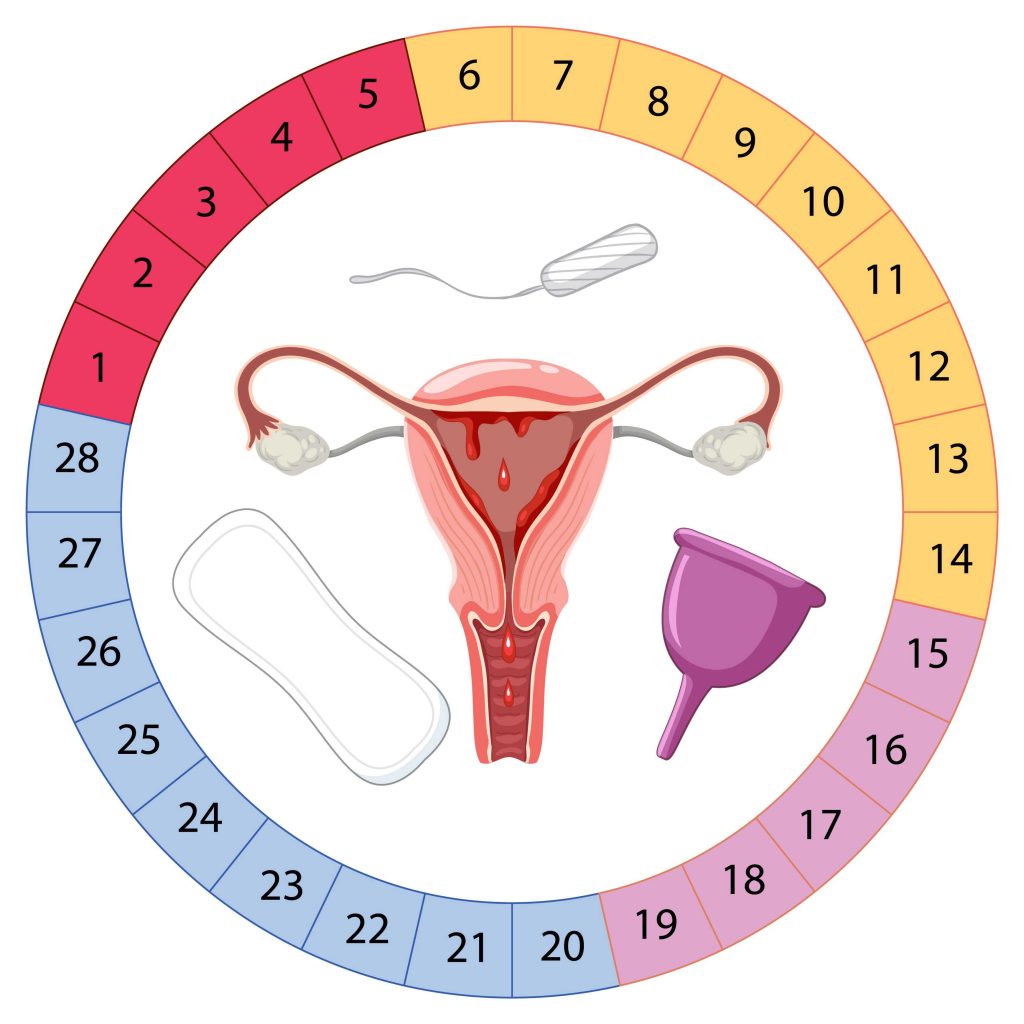

Growing up in my community, it was customary for girls to be sent away from home during their first menstrual period. Seclusion was deemed necessary, with the duration varying based on the menstrual cycle such as 21 days for the initial period, 15 days for the second, and 7 days for the third cycle. From the fourth cycle onwards, girls were allowed to stay in their own homes but had to isolate themselves from household chores and religious practices. I vividly remember the moment I gathered the courage to inform my mother about my first menstruation at the age of 11. Meaanwhile, my father arrived home with sweets for me from the market. However, when my mother shared the news with him, he found it hard to believe, insisting that I was not yet at the age of menstruation.

Following the customary practice, I was sent to a neighbor’s home during my menarche, not staying far from my own home. However, defying tradition, I was brought back home after just seven days of seclusion following my first cycle. This departure from the norm also meant that my four younger sisters were spared from the same experience. Our family realized the need to question and abandon blindly following such traditions, leading us to break free from isolation.

It is disheartening to acknowledge that many parts of the world still hold onto these detrimental practices. The chhaupadi custom, which is still practiced in some parts of Nepal and has sadly resulted in the loss of many lives while also further disempowering women. These practices serve as a stark reminder that women’s empowerment is hindered by these harmful customs.

The urgent need to challenge and rectify these practices becomes evident. Education and awareness must take center stage in eradicating such harmful customs, allowing women to thrive and live without fear. Natural processes such as eating, breathing, and menstruation are essential for women’s survival. Yet, our society fails to fully accept and embrace these natural cycles, subjecting women to stigma and problems associated with menstruation.

In numerous places, women endure harassment and discrimination during menstruation, with some even being secluded in menstrual huts during the period. Basic rights such as access to essential healthcare, hygiene, nutrition, rest, and minimum standards during menstruation are still lacking for many women.

It is important to acknowledge that the burden of menstrual poverty disproportionately affects marginalized communities. Women and girls from low-income backgrounds often struggle to afford menstrual hygiene products, resulting in the use of unhygienic alternatives or resorting to ineffective methods such as rags, leaves, or even ash. This not only compromises their physical health but also perpetuates the cycle of poverty and reinforces existing inequalities.

Moreover, the lack of access to proper sanitation facilities aggravates the challenges faced by menstruating individuals. In many regions, adequate toilet facilities with clean water, privacy, and proper disposal systems are unavailable, forcing women and girls to resort to unsafe and unhygienic practices. This not only increases the risk of infections but also restricts their mobility and participation in various aspects of life, including education and employment.

This cannot be solely attributed to religious beliefs, as even some men who consider themselves modern and educated perpetuate the treatment of their wives, sisters, and daughters as impure during menstruation. Shockingly, even some modern literature supports isolating and mistreating, menstruating girls and women, further reinforcing the stigma associated with menstruation. These practices and beliefs belittle the struggles faced by women during menstruation.

According to the United Nations, approximately 500 million women and adolescents worldwide lack access to adequate facilities for managing their menstruation, let alone menstrual health services. This dire situation, termed “menstrual poverty,” has become a grave concern, especially in developing countries like Nepal. Startlingly, government data reveals that only 15% of adolescent girls in Nepal use sanitary pads during menstruation. While sexual and reproductive health education is included in school curricula, it remains insufficient and superficial. Practical life skills taught by teachers often lead to embarrassment and reluctance from both educators and students.

While some public schools in urban areas provide free sanitary pads and safe toilet facilities for proper pad disposal, this remains an unattainable dream for girls in rural areas. The provision of free pads and comprehensive menstrual education in schools is lacking, with inadequate availability of separate toilets for girls. Consequently, many menstruating students in our country continue to face obstacles in attending school regularly.

Even though we have entered the second decade of the 21st century, menstruation is still met with ignorance and negativity in our society, subjecting approximately half of the population to undignified and unsafe living conditions. It is imperative to make concerted efforts at all levels to ensure dignified, safe, and healthy menstruation.

While the Muluki Ain (National Code) of 2074 has deemed all forms of discrimination, harassment, and inhumane treatment related to menstruation punishable, the National Menstrual Hygiene Management Policy of 2075 highlights the persistence of ignorance, discrimination, and disgust surrounding menstruation in various communities in Nepal. Menstrual blood is still considered impure, leading to shame, discrimination, untouchability, and pollution. The alarming statistic of only 15% of adolescent girls using sanitary pads in a country like Nepal highlights the horrifying condition of menstrual poverty. Menstruation impacts women’s lives, causing embarrassment, hindering work or study, creating insecurity at school or the workplace, and generating situations of abuse and low self-esteem. The limited resources for proper management of menstrual hygiene exacerbate social and economic inequality among women.

Addressing these issues requires collective responsibility from women themselves, parents, community leaders, politicians, and government agencies. It is crucial for our representatives, leaders, and health workers advocating for women’s rights and public health to genuinely comprehend the divisions and stigma faced by women during menstruation. As we strive for progress, it remains a thought-provoking question whether our leaders prioritize menstrual hygiene, despite every local level now having at least two women representatives.

Recently, the European country of Spain passed a law granting women a three-day leave during their menstrual cycle. Women in Spain can now take additional two days off, up to a total of five days, according to their individual needs. Similar laws exist in countries such as Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and even in African countries like Zambia, allowing women to take menstrual leave in their workplaces.

The concept of taking menstrual leave may seem unexpected, especially considering the experiences of Nepali women who endure undignified, unhealthy, unhygienic, and painful situations during their menstrual cycles. However, if society aims to become civilized, respectful, and progressive with minimum human standards, it is essential to put an end to primitive behaviors and ensure cleanliness and respect towards women during their monthly menstruation.

My personal journey has exposed the urgent need for positive change, for society to break the silence, challenge harmful traditions, and work towards a future where menstruation is embraced with dignity, safety, and inclusivity. It is time to ensure that every woman has access to the basic necessities and rights during menstruation, fostering an environment where women can thrive, free from the burdensome weight of stigma and discrimination.

Comments