At Nepal’s community schools, politicking takes precedence over educational development

School management committees across the country have turned into tools to exercise power. As a result, corruption and irregularities abound, while educational development takes a back seat.

The Rupandehi-based Santeshwar Basic School management committee held an election after efforts to unanimously select its office bearers yielded no result. In the election, the Janamat Party’s Rohit Prasad Gupta edged the by four votes. “It’s not entirely my desire to head the committee,” says Gupta, now the chair of the school located in Mayadevi Rural Municipality-2. “But the party requested me and the villagers backed me.”

Meanwhile, at the Kedar Secondary in Solukhumbu’s Nechasalyan Rural Municipality-4, the election of the school management committee reminded one of parliamentary elections. In the election held in Baisakh, 2080 BS, the Nepali Congress-backed candidate Hem Raj Kattel defeated UML’s Jagannath Bastola. Lekhnath Kattel, the school’s principal, says that even if the existing laws on education do not envision an election of a school management committee, elections are inevitable since there’s no consensus.

Students of the Rastriya Secondary School at Samsi Rural Municipality in Mahottari are pictured taking a class recently. The school, which has been without a management committee for six years, lacks essential infrastructure for the teaching-learning process.

Like in Santeshwar and Kedar schools, political parties are dominant in school management committee elections around the country. As a result, elections are held to pick office bearers of school management committees.

Nepal’s Education Act has mandated the provision of a management committee in each school for the institution’s operation, monitoring and management. The committee, which is selected with the guardians’ participation, can have local intellectuals, education lovers, those who have helped the school, and the school’s founders as members. But political parties tend to pick people loyal to them.

No cooperation, only intervention

Because of the intervention of the political parties, as many as 5,307 schools out of 28,761 around the country are yet to get a management committee. The Rastriya Secondary School at the Parsa Dewad village in Mahottari’s Samsi Rural Municipality, for instance, has been without a management committee for six years. The school’s principal, Rambabu Yadav, says that the school has lost a lot of opportunities because of a lack of the management committee. “The school, which has around 1,800 students, remains ill-managed,” Yadav said.

The Janamat Party’s Rohit Prasad Gupta (second from left) poses for a photo after he is elected the chair of the management committee of Santeshwar Basic School in Rupandehi. He is flanked by other newly elected members of the committee.

The school does not have enough classrooms and so, children are compelled to sit on the dusty floors. There is no proper drinking water system, nor a usable toilet. The school hasn’t been able to hire a teacher on grant. There has not been any progress on a building to be constructed under the President Educational Reform programme. The management committee’s decision is important to carry out all these works.

“I have repeatedly called the guardians for a meeting to form the management committee,” Yadav said. “But because of discord along party lines, we can’t reach a consensus.” Five out of twenty schools in Rupandehi’s Mayadevi Rural Municipality are without a management committee.

The rural municipality’s education officer Narayan Lamichhane says, “Initially, it takes time to forge a consensus. And when we can’t reach one, we have to go to elections, which prolongs the process and hence, the management committee isn’t formed for months.” Schools need to hold multiple meetings between political parties, local unit officials, security and local administration for a consensus to even go to elections.

At Sundi Secondary, another school in Mayadevi, though the guardians selected four members for the committee, there were debates about selecting the two, hence the committee has remained without a chairperson for four months. The Education Act mandates that the chairperson is selected after all the members are finalised.

“We tried to set a good precedent by selecting the members of the management committee through a consensus but we couldn’t,” says ward chair Arun Kumar Tiwari. He adds that of the two members selected by the guardians, there are one each from the Nepali Congress, Rastriya Prajatantra Party, and Loktantrik Samajbadi Party, while one is an independent. But there are disagreements about the rest of the two candidates.

While schools are in disarray for a lack of management committees for years, local units, which are responsible for school education, appear indifferent. The Education Act allows local units to form temporary committees in case school management committees aren’t formed in time. Moreover, local units can form their own Acts, directives and working procedures to ease the process of school management committee formation.

18.5 percent of schools without management committees

According to the Centre for Education and Human resource Development under the Education Ministry, a total of 18.5 percent of community schools had yet to get school management committees in the academic year 2079 BS. Over half of the schools in Madhesh Province are without one; of the 3,596 schools in the province, 1,988, or 55.3 percent, do not have a management committee yet. In Karnali, which fares the best among the provinces, of the 3,026 schools, 2,741, or 90.6, have a management committee.

Meanwhile, a dispute over the school management committee turned deadly at Madan Aashrit Basic School in Dhanusa’s Sabaila Municipality-1. Two people were killed in the incident 10 years ago. After which, the ward chair was entrusted with the responsibility of the chair of the school management committee but the school doesn’t have a management committee for the past three years, according to principal Meena Kumari Sah. According to Pradeep Mukhiya, chief of the municipality’s education department, 13 of the 25 schools in the municipality are without a management committee.

The Education Act has set the school management committee’s work, duties and rights. It mentions that to maintain a healthy education environment, there shouldn’t be religious, political or communal intervention in the school. But the formation of the management committee usually takes political colour.

Butwal’s Kanti Secondary, which with 5,173 students is perhaps the country’s fourth largest school in terms of student number, is also without a management committee. The formation of the committee has been in limbo due to conflict of interests between the Nepali Congress, UML and Maoist Centre.

The Congress and Maoist Centre are both seeking to lead the school, which was run by UML for over two decades. Because Butwal Sub-metropolis and the ward where the school is located both are led by the Congress, the party claims that it should also get a chance to lead the school. Meanwhile, the UML doesn’t want to let go of its leadership. The Maoist Centre, meanwhile, is looking to benefit from the conflict between the two.

“The conflict between the parties has hampered the school’s education,” says Mahendra Pandey, a civil society leader. “This over-politicisation has weakened community school education.”

Meanwhile, on Jestha 13, the local leaders of political parties formed a task force to constitute the school management committee. The task force includes Narishwar Sharma Poudel, who hails from Butwal-4 representing Congress, former ward chair Tanka Parajuli from UML and chair of ward 3 Bishnu Dhakal from Maoist Centre.

According to Butwal’s City Education Act 2074, the guardians can select the four members of the school management committee at any time. But the political parties have barred the guardians from doing so until the chair is selected. Loknath Gyawali, chair of Nepal Guardians’ Association, Rupandehi, says that parties are aiming to pick a political party-affiliated person as the chair. “This is politics over childrens’ future,” Gyawali said.

What are the parties’ interests?

The main reason behind the battle among political parties to select their representatives at community school management committees is the lure of economic resources. Experts say the parties aim to benefit from the large amounts allocated for construction projects like buildings at the schools. Moreover, once they have their people at the management committees, the parties can recruit teachers loyal to them. They also aim to influence the guardians and benefit at other elections.

Hemraj Kattel, President and Lekhnath Kattel Principal, Kedar Secondary School , Solukhumbu

Ram Binayak Singh, the chief of the Education Development and Coordination Unit, sees economic and political benefits as the main reasons behind the disputes in forming school management committees. That there are frequent complaints regarding embezzlement of funds in the mid-day meal scheme and construction projects and irregularities in scholarship schemes confirm this, according to Singh.

Professor Ananda Man Singh Shakya says that with political intervention, the parties are taking the agencies of the guardians away. “This is dishonesty towards education,” Shakya says. “You don’t want to invest in education but go to any length to fill schools with your own people?”

The Nepal government has vowed to keep schools away from politics by issuing the Schools Zone Of Peace (SZOP) National Framework and Implementation Guideline, 2068. And Nepal’s political parties have accepted schools as zones of peace. But to appoint those who are loyal to one’s party to the management committee, they go to any length, often resorting to violence. “The political parties say one thing and do quite the opposite, and Nepal’s education sector is bearing the brunt of that,” says Meena Sharma, an activist under the Schools Zone of Peace campaign. “They are quite wittingly putting the futures of students on the line.”

The Education Act has granted management committees the responsibilities to mobilise resources to operate schools, keep record of and protect the assets, update physical and economic statistics, endorse the school’s annual budget and inform the local unit about it, recruit teachers and recommend teachers for posting, among others.

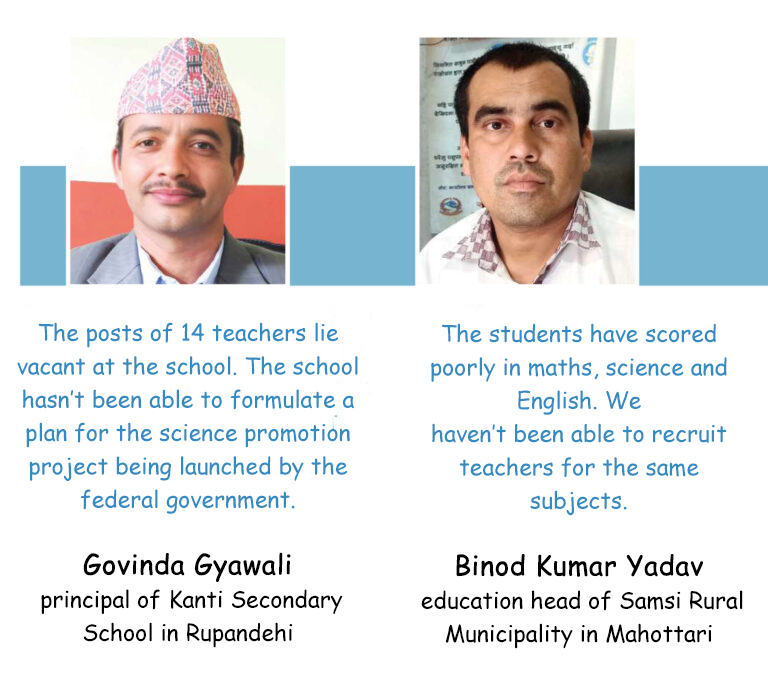

In Mahottari’s Samsi Rural Municipality, six of seven schools are without a management committee; as a result, the grant budget for physical infrastructure and teaching-learning received from the federal government is getting frozen, says the education officer of the rural municipality Binod Kumar Yadav. Yadav says that the lack of the management committee was also reflected in the schools’ poor SEE results. “The students scored poorly in math, science and English because of a lack of specialised teachers,” Yadav says.

According to Sitesh Kumar Yadav, the technical assistant of Durga Bhagwati Rural Municipality in Rautahat, 12 students at the local unit have yet to get school management committees; as a result, the hiring of contract teachers has been halted for a long time.

In Butwal’s Kanti Secondary, the post of 14 teachers lies vacant. Because of a lack of the management committee, the exams for the posts remain in limbo, even though the vacancy was announced for 10 teachers in Chaitra. The school hasn’t been able to submit its application for the science promotion plan. The school is also facing myriad other problems in administration and educational management, says principal Govinda Gyawali.

Gyawali adds that the school was disqualified from the model school selection competition due to the delay in forming a school management committee in 2073 BS. Even though the school was ahead of competitors in all indicators, it had to withdraw from the competition as complaints were filed regarding the lack of a management committee.

Meanwhile, Pradeep Mukhiya, the education officer of Sabaila Municipality in Dhanusha, says that the schools in the local unit are facing problems in recruiting grant teachers, monitoring administrative works in the schools, constructing infrastructures and launching educational activities. “The management committee is tasked with managing the mid-day meal programme and distributing sanitary pads but it is yet to be formed,” Mukhiya said.

Silver linings

Nepal’s constitution has granted the right for improving school education to local units. And some local units have performed well in constituting the school management committees.

Dhanusha’s Ganeshman Charnath Municipality has formulated a rule that the children of those picked as members of the school management committee should be regular students. According to Chhoti Mukhiya, education officer of the municipality, since the inclusion of the rule that the guardians of children with the highest attendance would be selected as committee members in the City Education Act, there is no dispute regarding who would be picked at the committee. “We form a new committee within two months of the expiry of the old one,” Mukhiya said, adding that they haven’t held an election to form the committee yet.

Meanwhile, Bardiya’s Thakurbaba Municipality has introduced a law wherein the people’s representative would be the chair of the school management committee so it doesn’t remain vacant. Following disputes over the formation of the committee, a provision to appoint the people’s representative recommended by the ward committee was included in the City Education Act, according to Ramhari Rijal, the municipality’s chief administrative officer. A writ petition that said the Act went against the federal law was filed at the High Court in Tulsipur . But the court dismissed the petition and the Act is currently in effect.

Rijal said that since the people’s representative was the chair of the school management committee, the budget being disbursed for schools from municipalities and wards has increased and issues regarding schools are being discussed at municipal meetings. “We have been following the federal law mandating the school management committee have at least four guardians as members,” Rijal said.

According to educationist Prof. Ananda Man Singh Shakya, to keep the school management committee away from party politics, there should be a provision where only the guardian can be the committee chair. He believes that having the people’s representative as chair of the committee opens the door for party politics. “The support from the guardians and the community is essential for school operation,” Shakya says. “To increase community participation, a separate technical suggestion committee can be formed.”

Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, education head of Kapilvastu’s Buddhabhumi Municipality, also suggests that a school management committee composed of people’s representatives, local education lovers, and social workers would be ideal.

Keshav Dahal, the spokesperson for the education ministry, says that while the chairs of the school management committees should be guided by service motive, politics has become the dominant force, hence school administrations are in disarray. Education Secretary Deepak Kafle says that the local units and community leaders should play a proactive role in keeping schools away from political intervention. “We have received complaints that there is political intervention in the formation of school management committees,” he said.

Educationist Prof. Dr. Bidyanath Koirala says that the education sector hasn’t been reformed because of politicking in the formation of school management committees. “The intervention of political parties has reached school management committees,” Koirala says. “The benefit of students is only possible if schools are kept away from party interests.” He believes that the formation of school management committees wouldn’t be controversial if good practices like the Education Acts formed by local units are followed by all.

Comments